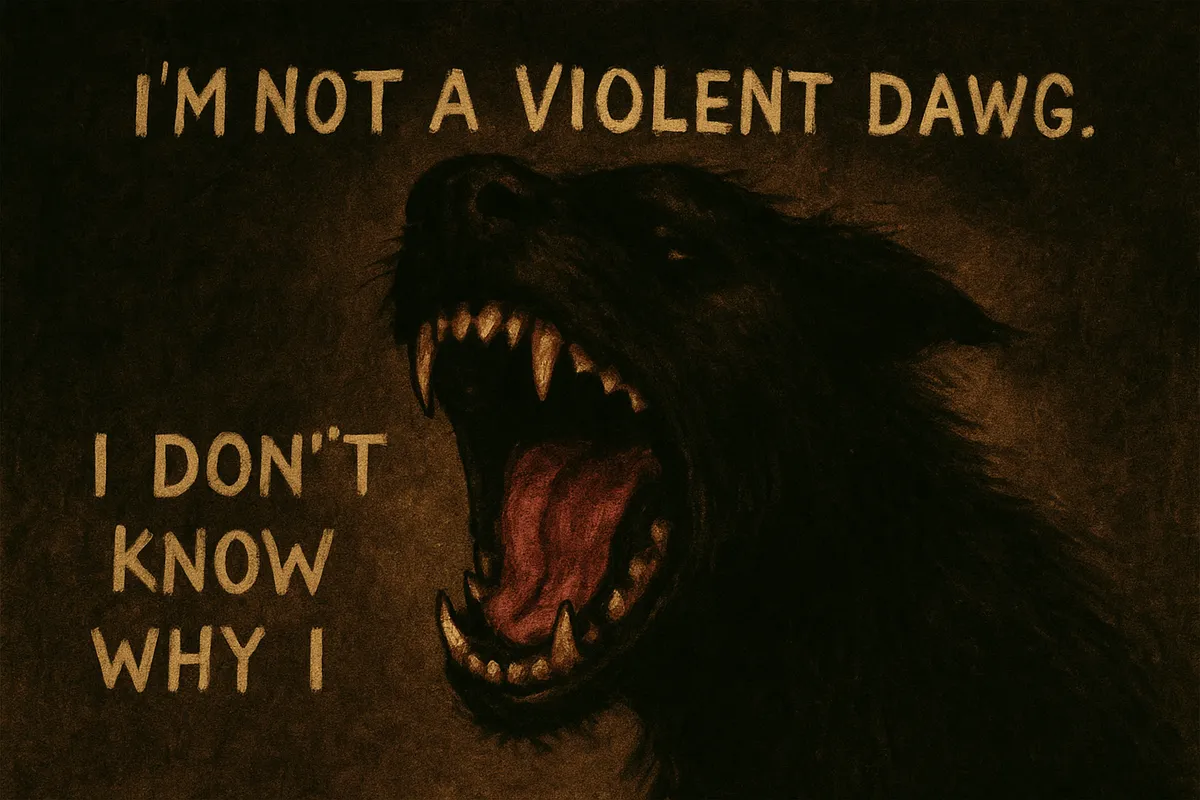

I have always thought of myself as someone who does not bite. This is a story about being wrong.

The facts are these: I move through the world quietly. I avoid confrontation. When asked to describe my temperament, I use words like “even-keeled” and “reasonable.” I have built an entire self-concept around the idea that I am not the kind of person who hurts others deliberately. I have been, it turns out, operating under a fundamental misapprehension.

The evidence suggests otherwise.

On the Nature of Self-Reporting

It occurs to me that we are perhaps the least reliable witnesses to our own behavior. We see ourselves in the abstract, in our intentions rather than our actions. We catalog our good impulses and file away our bad ones as aberrations, statistical noise in the data of our essential character.

Consider this: I can recall with perfect clarity every instance when someone else has been unnecessarily cruel to me. I can remember the exact words, the tone, the way their cruelty landed and where I felt it in my body. Yet when I try to catalog my own moments of cruelty, the list grows mysteriously short. Not because I am kinder than those who have hurt me, but because I am, like most people, exceptionally skilled at not seeing what I do not wish to see.

The bite, when it comes, feels like surprise. Like something happening to me rather than something I am doing. This is, I suspect, how most violence feels to the person committing it: sudden, inexplicable, somehow external to their understanding of who they are.

The Mechanics of Contradiction

There is a moment that precedes the bite. I have learned to recognize it now, though recognition and prevention are different skills entirely. The moment feels like a door opening onto a room I did not know existed in the house of myself. The person who enters that room is someone I do not particularly like or understand.

This other person operates with a different set of priorities. Where I value kindness, this person values victory. Where I prefer understanding, this person chooses punishment. Where I aim to build, this person seems perfectly comfortable tearing down. The transition between these two versions happens so quickly that I often miss it entirely, aware only that the conversation has taken a turn I did not intend and cannot easily reverse.

The most unsettling aspect of this experience is not the cruelty itself but the competence with which it is executed. The person who emerges in these moments knows exactly where to apply pressure, exactly which words will cause the most damage. This suggests that the capacity for harm was always there, waiting, cataloged and ready for deployment.

On the Question of Intent

Intent, I have discovered, is a complicated thing. I do not intend to hurt people. I do not wake up in the morning planning cruelty. Yet intention and impact occupy different territories entirely, and the border between them is more porous than I once believed.

When I bite, I am usually trying to protect something. Myself, my position, my understanding of how things should be. The harm I cause feels incidental to these more pressing concerns. I am not trying to wound; I am trying to win, or to escape, or to establish some version of truth that feels essential in the moment.

This distinction probably matters less to the person being bitten than it does to me.

The Aftermath of Recognition

Once you see yourself clearly, you cannot unsee it. This is both a blessing and a burden. The blessing is obvious: awareness creates the possibility of choice. The burden is that you must now live with the knowledge of your own capacity for harm, must carry the weight of understanding that you are not who you thought you were.

I find myself now constantly monitoring, constantly checking the temperature of my responses, constantly asking whether the person speaking is the person I want to be. This hypervigilance is exhausting but seems necessary. The alternative is to return to the comfortable fiction that I am simply not the kind of person who bites.

The truth is more complicated and less flattering: I am exactly the kind of person who bites, who just happens to spend most of my time trying not to.

The Economy of Harm

There is, I think, an economy of harm that governs all human interaction. We are constantly making small withdrawals and deposits from accounts we do not fully understand. A moment of kindness here, a casual cruelty there. Most of us operate with a vague sense that we are probably in the black, that our good actions outweigh our bad ones, that we are fundamentally decent people who occasionally make mistakes.

But what if the accounting is different than we imagine? What if the harm we cause registers more clearly than the good? What if the people we have bitten remember those moments with the same clarity with which we remember being bitten ourselves?

This is a disturbing line of inquiry. It suggests that we might be carrying debts we did not know we had incurred, that our self-image might be built on a foundation of selective memory and strategic forgetting.

On the Practice of Attention

I am trying now to pay closer attention. Not just to the moments when I bite, but to the moments that precede the biting. The way the air changes. The shift in my breathing. The particular quality of anger that feels like righteousness but might be something else entirely.

Attention, it turns out, is a skill like any other. It can be developed, refined, strengthened through practice. The more carefully I watch myself, the more clearly I can see the choice points, the moments when I might choose differently, the spaces between impulse and action where change becomes possible.

This is slow work. There are still days when I discover, hours later, that I have bitten someone without noticing. There are still conversations I leave feeling like I have been taken over by someone else, some angrier, smaller version of myself that I do not recognize but apparently am.

The Persistence of the Problem

Perhaps the most honest thing I can say is this: I do not know how to solve this problem completely. I do not know how to become someone who never bites, because I am not convinced that such a person exists. What I am learning is how to become someone who bites less frequently, less deeply, with more awareness of what I am doing and why.

This feels like progress, though it is not the kind of progress that makes for easy stories. It is messy, incomplete, ongoing. It requires me to hold two contradictory truths simultaneously: that I am not a violent person, and that I am sometimes violent. That I am kind, and that I am sometimes cruel. That I am someone who builds, and that I am sometimes someone who destroys.

The work is learning to live with this contradiction without letting it paralyze me, without using it as an excuse to stop trying to be better.

The Acceptance of Complexity

We are, all of us, more complex than our stories about ourselves allow. We contain multitudes, not all of them flattering. The person who is capable of great kindness is often the same person who is capable of great cruelty. The person who builds beautiful things is often the same person who sometimes tears them down.

I am not a violent dawg. I am also not a peaceful one. I am something messier, more contradictory, more human than either of those simple designations would suggest. I am someone who tries to be good and sometimes fails. Someone who wants to do no harm and sometimes does it anyway. Someone who is still learning the difference between who I think I am and who I actually am.

The distance between these two versions of myself is where the real work happens. It is where choice lives, where change becomes possible, where the person I want to be meets the person I sometimes am and tries to find a way forward that honors both the aspiration and the reality.

I am still learning. I am still trying. I am still, sometimes, biting. But I am also still here, still paying attention, still believing that awareness is the first step toward something better.

The story continues, imperfectly, with attention as the only tool I have found that works, and the hope that seeing clearly is the beginning of choosing differently.