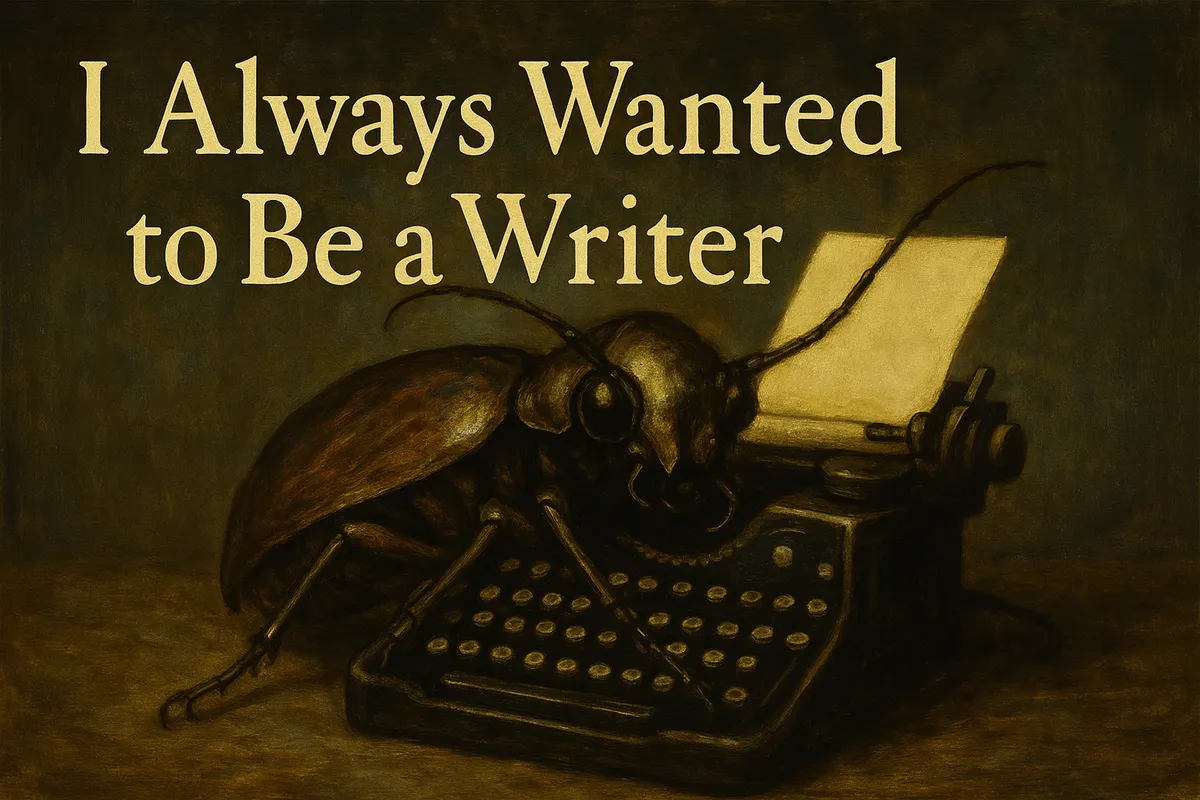

I Always Wanted to Be a Writer

The desire came to me like a fever, or perhaps like that peculiar certainty Dostoevsky’s underground man possessed about his own suffering: absolute, irrational, and impossible to shake. I wanted to write not because I had anything particularly profound to say, but because I sensed there were chambers in the human soul that could only be unlocked through the strange alchemy of putting words to paper.

I carried notebooks then, small black ones that grew heavy with the weight of observations I couldn’t quite articulate. Fragments of conversations overheard on metro platforms. The way a stranger’s face crumpled when they thought no one was watching. The precise quality of light that made ordinary rooms feel haunted. I collected these moments like evidence of some crime I couldn’t name, some truth that hovered just beyond my ability to grasp it.

But there was something Kafkaesque about the whole endeavor. The more I wrote, the more the meaning seemed to recede. Each word I captured felt like a betrayal of the original experience. How do you describe the color of loneliness? How do you render in language the exact texture of despair that settles over a person waiting for a train that may never come?

The Underground Chambers Where Writers Live

Dostoevsky understood something about writers that we rarely admit: we are creatures of the underground, dwelling in the psychological basements of experience, mapping the territories that polite society prefers to ignore. We are drawn to the spaces between certainty and doubt, between sanity and madness, between what people say they feel and what they actually feel.

The writers I admired most were the ones who descended deepest into these chambers. Kafka, transforming the bureaucratic nightmare of modern existence into myths that somehow explained everything about being human. Dostoevsky, excavating the moral complexities of the human heart with the precision of an archaeologist and the passion of a madman.

They wrote from a place of profound unease, a sense that something was fundamentally wrong with the world and that only by examining this wrongness in excruciating detail could they hope to understand it. Their notebooks weren’t filled with beautiful observations about sunsets. They were field reports from the front lines of human consciousness.

Important (The Weight of Psychological Truth)

“I am a sick man… I am a spiteful man. I am an unattractive man.” Dostoevsky’s underground man begins his confession with brutal honesty about his own nature. True writers, the ones who matter, start from this place of unflinching self-examination. They don’t write to be liked or admired. They write to understand the incomprehensible machinery of human existence.

Writers Who Die Young, Leaving Behind Maps of Interior Countries

When writers die young, they leave behind something more precious than finished works. They leave behind maps of interior countries that only they had the courage to explore. Kafka’s incomplete novels aren’t just fragments; they’re detailed surveys of psychological territories that didn’t exist until he charted them.

There’s something almost mystical about the incompleteness. The Castle that K. never reaches. The trial that Josef K. never understands. Raskolnikov’s punishment that somehow feels insufficient for the magnitude of his crime. These unfinished journeys reflect something true about human experience—that we are all traveling toward destinations we’ll never reach, seeking answers to questions we can’t properly formulate.

But maybe this is why their work feels so urgently alive. They wrote with the intensity of people who knew they were running out of time to solve the unsolvable puzzle of human existence. Every sentence carried the weight of mortality, not just their own, but the mortality of every consciousness that struggles to make sense of its brief, bewildering passage through the world.

The Metamorphosis of Daily Life

I stopped carrying notebooks for a while because I became afraid of what I was finding in them. Like Gregor Samsa waking up to discover his transformation, I realized that the act of paying attention—really paying attention—changes you in ways you can’t undo. Once you start seeing the absurdity, the hidden violence, the quiet desperation that underlies so much of ordinary life, you can’t unsee it.

There’s a reason Kafka worked in an insurance office and Dostoevsky was a compulsive gambler. The extremity of their inner lives required the ballast of mundane reality. But it also meant they could see the strangeness lurking beneath the surface of the everyday world. The way a bureaucratic procedure could become a form of torture. The way a simple moral choice could split a soul in half.

I think this is what I was really afraid of when I stopped writing. Not that my words weren’t good enough, but that the act of writing would force me to confront truths about existence that I wasn’t ready to face. That paying attention to the world with the intensity that real writing requires would reveal too much about the fundamental absurdity of being human.

The Underground Man’s Dilemma

Dostoevsky’s underground man faces a terrible choice: he can remain in his underground chamber, analyzing his own psychology with savage precision but never acting, or he can emerge into the world and discover that action without understanding is equally futile. This is the writer’s dilemma too. We can descend so deep into the analysis of experience that we become paralyzed by the complexity of what we find there.

I spent years in my own underground chambers, filling notebooks with observations that grew increasingly baroque and self-referential. I analyzed my own motivations until they became incomprehensible to me. I dissected my relationships until they lay in pieces on the page, their original meaning lost in the autopsy.

But there’s something liberating about reaching the bottom of this descent. Once you’ve examined your own consciousness with sufficient ruthlessness, once you’ve admitted the full extent of your own contradictions and delusions, you can finally start writing with something approaching honesty.

The Bureaucracy of Dreams Deferred

Kafka understood that modern life is a vast bureaucratic machine designed to crush the human spirit through administrative procedures that make no sense but cannot be escaped. The same machinery that trapped Josef K. in his endless trial operates on our dreams and ambitions.

I think about all the forms I’ve filled out, all the meetings I’ve attended, all the energy I’ve spent navigating systems that seem designed to prevent the very thing they claim to facilitate. How many potential novels have been strangled by student loan paperwork? How many poems have died in performance reviews? How many stories have been lost to the simple exhaustion of trying to survive in a world that demands constant proof of productivity?

The tragedy isn’t just that writers die young. It’s that so many potential writers die before they ever start writing, crushed by the weight of maintaining their position in a society that has no real place for the kind of truth-telling that literature requires.

The Strange Salvation of Putting Truth to Paper

But here’s what Dostoevsky knew that the underground man struggled to learn: confession, even confession to an empty page, has a kind of redemptive power. Not because it makes you a better person, but because it makes you a more honest one. And honesty, however ugly, is somehow more bearable than the alternative.

When I started writing again, I tried to write like Kafka, with the precision of someone documenting a bureaucratic nightmare that might also be a spiritual condition. I tried to write like Dostoevsky, with the psychological acuity of someone who has looked into the abyss of human motivation and found it both terrifying and strangely beautiful.

The notebooks filled up again, but the quality of the observations changed. Instead of trying to capture beauty, I tried to capture truth. Instead of describing what I thought I should see, I described what I actually saw—the cruelty that masquerades as kindness, the fear that drives what we call ambition, the desperate loneliness that underlies most human connection.

Note (The Underground Truth)

“Can a man of perception respect himself at all?” Dostoevsky’s underground man asks this question knowing that the answer is probably no. But perhaps the real question is: can a man of perception do anything but write? Can someone who has seen too much of human nature do anything but try to find language for what they’ve witnessed?

The Metamorphosis of Memory

Memory, I’ve discovered, is its own kind of Kafkaesque bureaucracy. The more precisely you try to recall an experience, the more it transforms under scrutiny. The harder you try to preserve a moment, the more it insists on changing into something else entirely.

This is perhaps why the writers who died young left behind such haunting fragments. They captured their memories before they could completely transform, before the bureaucracy of retrospection could process them into something more palatable. Their work retains the raw urgency of experience that hasn’t yet been explained away or rationalized.

I think about Kafka’s letter to his father, that brutal 100-page examination of a relationship that shaped his entire psychological landscape. He never sent it, of course. It was too honest, too uncompromising in its assessment of the damage that love can do. But in writing it, he created something more valuable than a reconciliation: he created a map of the territory where parent and child inflict their deepest wounds on each other.

The Weight of Unfinished Business

Every writer dies with unfinished business. Not just the novels that remain unwritten, but the psychological mysteries that remain unsolved. Dostoevsky spent his entire career trying to understand the mechanics of redemption: how a soul moves from sin to salvation, what role suffering plays in moral transformation. He never quite solved it, but his failure to solve it produced some of the most psychologically complex literature ever written.

Kafka died with three unfinished novels, each one a different attempt to map the relationship between individual consciousness and the incomprehensible systems that govern modern life. The fact that none of them reach a conclusion seems less like a failure than like an accurate representation of the human condition. We are all living in unfinished novels, stories that will never reach a satisfying resolution.

Maybe this is what draws me back to writing despite all the fears and doubts: the recognition that incompleteness is not a bug in the system but a feature. The most honest thing a writer can do is document the ongoing failure to understand, the persistent attempt to make sense of experiences that resist explanation.

The Underground Railroad of Truth

Writing, I’ve come to believe, is a kind of underground railroad for truths that cannot be spoken aloud in polite society. Dostoevsky smuggled psychological insights past the censors of his time by embedding them in the consciousness of criminals and madmen. Kafka made the absurdity of modern bureaucracy visible by pushing it to its logical extreme.

They wrote in code, not because they wanted to be obscure, but because certain truths can only be approached obliquely. You can’t state directly that modern life is a kind of spiritual prison—you have to show a man waking up as an insect. You can’t simply declare that moral certainty is impossible—you have to follow a murderer through the labyrinth of his own justifications.

This is the tradition I want to join, not the tradition of beautiful writing or clever writing, but the tradition of necessary writing. Words that serve as vehicles for truths that have no other way to travel from one consciousness to another.

The Trial of Becoming a Writer

Like Josef K., I find myself on trial for crimes I can’t quite name. The crime of wanting to write when there are already too many books in the world. The crime of thinking my particular way of seeing might add something to the conversation. The crime of believing that the act of writing itself might be a form of resistance against the forces that would reduce human experience to statistics and productivity metrics.

The trial never ends, of course. Every time I sit down to write, I have to defend my right to add more words to a world already drowning in words. Every sentence feels like evidence presented to a jury that may not even exist, in service of a verdict that will never be delivered.

But perhaps this is precisely the point. Perhaps the trial is the thing itself. Perhaps the act of continuing to write despite the absence of clear justification is what transforms mere expression into something approaching literature.

The Castle I’m Still Trying to Reach

I still want to be a writer, but my understanding of what that means has changed. I no longer imagine myself producing works of transcendent beauty that will outlast civilization. Instead, I think of myself as a cartographer of psychological territories, someone who maps the underground chambers where human consciousness struggles with its own contradictions.

The castle I’m trying to reach is not fame or recognition or even understanding. It’s the simple goal of writing with enough honesty to justify the act of writing at all. To document the strangeness of being conscious in a universe that seems designed to make consciousness as difficult as possible.

Kafka’s K. never reaches his castle, but his failure to reach it tells us everything we need to know about the nature of human aspiration. Dostoevsky’s underground man never resolves his contradictions, but his inability to resolve them illuminates the fundamental contradictions that define human nature.

Maybe the writers who died young understood something that those of us who live longer struggle to accept: that the value of writing lies not in reaching destinations but in making the journey visible. Not in solving the puzzle of human existence but in documenting our attempts to solve it with as much precision and honesty as we can manage.

The notebooks are calling again. The underground chambers are waiting to be explored. And somewhere in the distance, barely visible through the fog of daily life, the castle stands. Unreachable but somehow essential, a destination that gives meaning to the journey even if we never arrive.

It’s time to descend again. Time to write from the underground. Time to document the ongoing trial of being human with all the psychological complexity it demands.

The writers who died young left us maps. Now it’s time to add our own cartographic notes to the territories they began to chart.

For Kafka, who showed us the absurdity. For Dostoevsky, who showed us the depths. For all the underground cartographers still mapping the unmappable territories of human consciousness.